Model evaluation is not just about a single score; it is about how a classifier behaves as the decision threshold changes. This matters when one class is rare, because “high accuracy” can still hide poor detection of the minority class. Two standard tools, the ROC curve and the precision–recall (PR) curve, help you compare models and choose thresholds more responsibly, a topic commonly covered in data science classes in Bangalore.

1) The key rates behind both curves

Both curves are built from the confusion matrix:

- TP (true positives): predicted positive and actually positive

- FP (false positives): predicted positive but actually negative

- TN (true negatives): predicted negative and actually negative

- FN (false negatives): predicted negative but actually positive

From these counts, we compute:

- Recall / TPR (true positive rate) = TP / (TP + FN)

- Precision = TP / (TP + FP)

- FPR (false positive rate) = FP / (FP + TN)

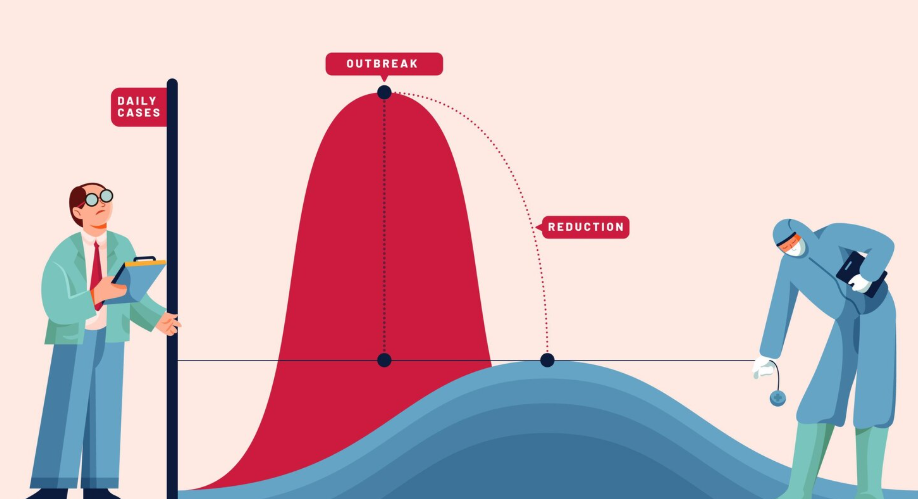

Most classifiers output a probability or score. If you lower the threshold, you label more cases as “positive”. Recall usually increases, but false positives can also increase. Curves summarise this trade-off across all thresholds instead of locking you into a default like 0.5.

2) ROC curve: strong for general separability, but can mislead under imbalance

The ROC curve plots TPR (recall) on the y-axis versus FPR on the x-axis across thresholds. It answers: “How well does the model separate positives from negatives, regardless of the exact threshold?”

A popular summary is AUC-ROC (area under the ROC curve). It measures ranking quality: the probability that the model assigns a higher score to a random positive instance than to a random negative instance. For many balanced or mildly imbalanced problems, ROC and AUC provide a stable, high-level view.

The limitation shows up with extreme imbalance. When negatives dominate, the FPR denominator (FP + TN) is huge, so FPR can remain small even if the model produces many false positives in absolute numbers. In real workflows, those false positives may still be expensive (manual review or wasted outreach). This is why practitioners, especially those trained in data science classes in Bangalore, treat ROC asa useful context, not the final answer for rare-event detection.

3) Precision–Recall curve: the right lens for rare positives

The PR curve plots precision (y-axis) versus recall (x-axis) across thresholds. It asks a more operational question for imbalanced tasks: “If I try to catch more positives, how trustworthy are my positive predictions?”

Precision directly reflects the false positive burden. If you flag 1,000 cases and only 100 are truly positive, precision is 10%, a clear signal of wasted effort. Recall tells you how much of the positive class you captured. In fraud, churn, medical screening, and security alerting (where positives are rare but important), PR curves often separate “good” models from “usable” ones more clearly than ROC curves.

A useful summary metric is Average Precision (AP), which approximates the area under the PR curve. Also, remember the baseline: the precision of a random classifier equals the prevalence of the positive class. If only 1% of cases are positive, a model must beat about 1% precision to be meaningful.

4) Choosing the right curve and setting a threshold

A practical rule of thumb:

- Use ROC when you want a broad view of separability or ranking, and class imbalance is not extreme.

- Use PR when positives are rare and false positives carrya real cost.

In many projects, the best approach is to look at both. ROC-AUC can confirm that a model ranks cases well overall, while the PR curve shows whether the “positive” predictions are workable in practice. This dual view is commonly recommended in data science classes in Bangalore.

Threshold selection should be driven by the problem, not by habit. Choose a target minimum precision (to control workload) or a target minimum recall (to avoid missing true cases), then select the threshold that meets that constraint on validation data. If you need a single threshold-based metric, compute F1 (balanced precision/recall) or Fβ (when recall matters more) at candidate thresholds.

Conclusion

ROC curves and PR curves come from the same confusion-matrix counts, but they spotlight different realities. ROC is a strong general-purpose tool for judging separability, while PR is usually more informative for highly imbalanced datasets where the positive class is the priority and false alarms are costly. For rare-event problems, lead with PR analysis and use ROC as a complementary check, an approach emphasised in data science classes in Bangalore because it aligns evaluation with real outcomes.